Why Taking Photographs Is Not Enough

Susan Sontag, photography, body of work, the faceless woman

I have been thinking a lot lately about what I am leaving behind as an artist.

Not in a morose or morbid way, but as a constructive and critical thought experiment.

What will I have made that is truly mine? What work will have mattered?

“The very nature of photography implies an equivocal relation to the photographer as auteur.”

—Susan Sontag, Photographic Evangels

Unlike a painter, whose brushstrokes are undeniably theirs, or a writer, whose voice is distinct, photography doesn’t always offer that same clarity of authorship. If I lay out all my past work, would it look like mine, or just like the work of any competent photographer of my time?

This question has been sitting with me for a while now, and it’s why I recently hit delete on so much of what was visible on my website. When I looked at those photos, I felt no connection to them. They weren’t a body of work—they were just work.

It is undeniable that a large part of my art after school was, in fact, work for clients. Unlike Jacques-Henri Lartigue, I didn’t have mom and dad to lean on so I could capture Belle Époque France. I didn’t have unlimited access to cameras or the freedom to experiment without financial pressure.

“The bigger and more varied the work done by a talented photographer, the more it seems to acquire a kind of corporate rather than an individual authorship.”

—Susan Sontag

I kept prioritizing safety and paying my bills over pursuing my artistic practice. I don’t think I am unique in this. I grew up in an immigrant house, with hardworking parents, who really did pull the line, “We didn’t move here for you to not be educated.”

Practicality was baked into my bones. Design over art. Artists don’t make money, but a designer can get a job. Design over photography. I bought a laptop in university thanks to working evenings and weekends, and I rode that thing until its deathbed ten years later. The thought of spending more money on a camera, plus the cost of film processing, seemed indulgent.

To set aside time for art meant squeezing it into the margins of the day. Painting on the floor of my living room was the one artistic luxury I gave myself. I lived in a basement suite of a hundred-year-old building, and I only had the space because I never bought a couch. I had one chair and a hand-me-down table to eat at. And as the years went on, it seemed like there would simply never be enough time or money to return to a practice I was excited about.

It wasn’t until I was in my thirties that I finally hit a wall and went out and bought a used camera from a local shop. I was intimidated by digital cameras, having learned on film. I was insecure in it all but excited. I spent the following years learning to shoot on digital, edit, and eventually share the work. Which led to the next hurdle in this story: social media.

I cannot only disparage Instagram; it was through it that I made friends who were light years ahead of me as photographers. I started to invest time to meet up, drive to the mountains, and go after what interested me. But it was also a time that was less about pursuing a project or idea and simply mucking about.

I looked around and saw photographers growing on Instagram and thought, Okay, that is what I should do. So I became a trend-following photographer. I chased what was popular, but I wasn’t thinking about why I was shooting—I was just reacting.

“Many of the published photographs by photography's greatest names seem like work that could have been done by another gifted professional of their period.”

—Susan Sontag

I look back at that time now, and I know I wasn’t pushing myself toward something meaningful. I was just trying to keep up.

That pattern followed me into my career. I rarely made intentional choices. Instead, I took what came. In fact, I didn’t even seriously shoot for a client until one outright asked me why I was hiring another photographer for the job.

Yes. It was like that.

I was so afraid of not being good enough that I would hire photographers to do jobs despite being a photographer myself.

I still think about that question. It tipped me into stepping forward and saying, I am a photographer. From restaurant shoots to product photography and everything in between, it became a part of my offering as a freelancer. My website morphed and began to show this work. And my confidence grew with it.

I soon became known for my product work. I went in-house with a brand, working on the design team, building sister brands, handling social media content, and doing photography. I was a little one-person content hub. From team headshots to website banner updates, I did it. It was fun.

But as this became the norm, and friends started to send me inspo videos on social media of other product photographers because they thought I would like it, I realized how uninterested I was.

“It requires a formal conceit (like Todd Walker’s solarized photographs or Duane Michal’s narrative-sequence photographs) or a thematic obsession (like Eakins with the male nude or Laughlin with the Old South) to make work easily recognizable.”

—Susan Sontag

I had neither. My work had no clear identity, no defining theme, no personal fingerprint. I had been practical. I had been adaptable. But I had never been singular.

I realized then that I had been influenced into being practical yet again.

“For photographers that do not limit themselves, their body of work does not have the same integrity as does comparably varied work in other art forms.”

—Susan Sontag

I had spent years making images, but I had never really committed to a point of view. I was practical, but I was not deliberate. I took the work that came, but I never asked myself: What do I want to say?

So, I started deleting. Not because I hated my past work, but because I wanted to create space for something new.

I am only now thinking about collections, having a couple of ongoing projects, and perhaps even obsessions. But for the first time, I am starting to think beyond this phase.

Every artist grows and changes. But this time, I refuse to let practicality dictate my choices.

I am not that little immigrant girl in the basement suite anymore. I don’t have to choose survival over creation.

And this time, I am making work that feels like mine.

Thanks for reading! This year, I’m exploring slow creativity—what it means to work with time instead of against it. If that resonates, consider subscribing for free.

Personal Work

Door No. 14. Part of an ongoing series that started unintentionally and grew over the years. A portal into someone’s life—one we often pass by without a second thought. But behind it, a whole world we’ll never see.

Recommended Reading

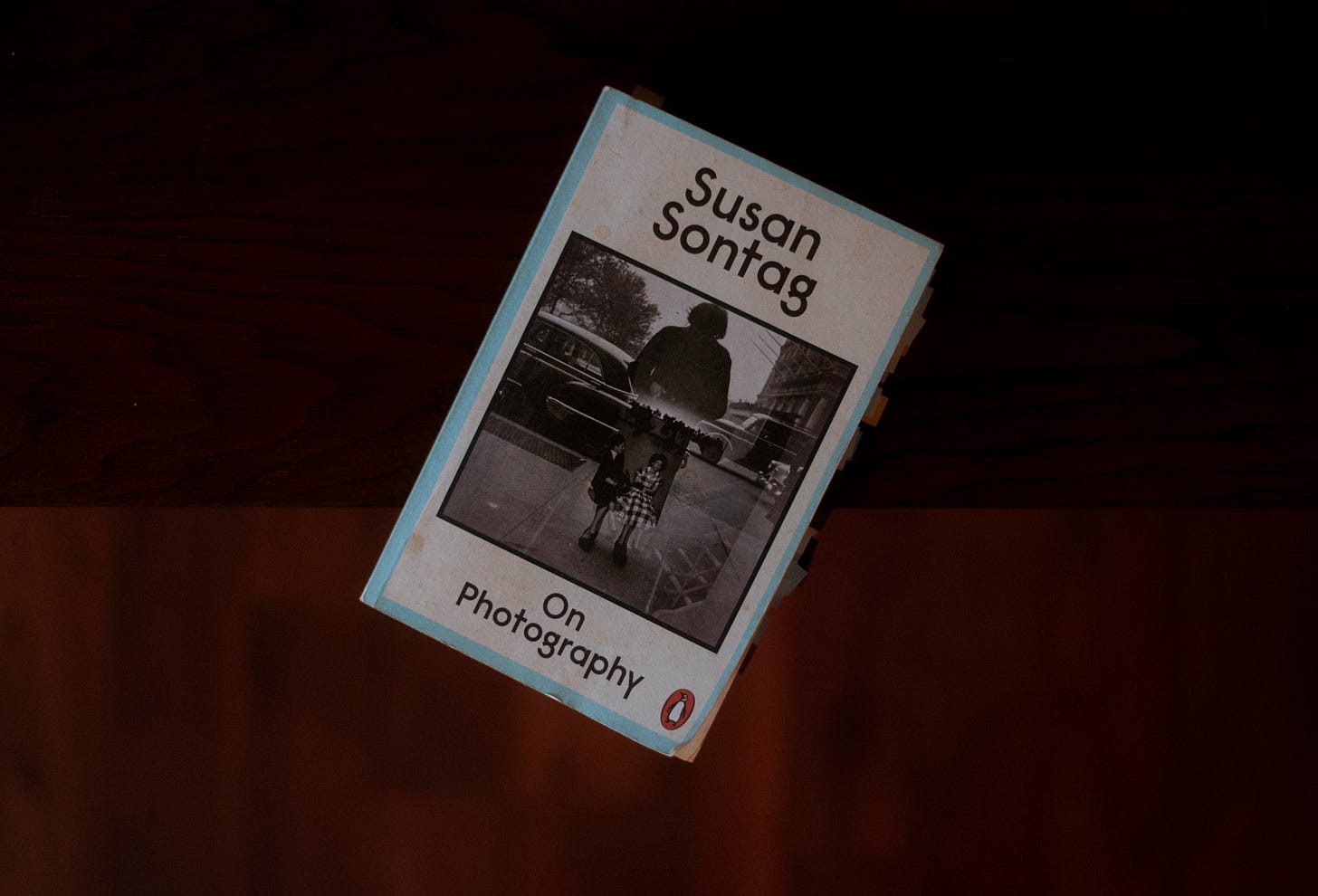

On Photography

Susan Sontag

The essays in On Photography really made me sit back and think about my work and photography as a whole. I wouldn’t recommend swallowing Sontag’s ideas whole, but rather using them as a starting point to consider what photography means—to you, to culture. What does it mean to take a photo? Why do we do it? How do images inform our biases? On and on.

I took my time reading this, one essay at a time, and I know I’ll return to sections as time goes on. Written in the 1970s, so much of what she says still feels relevant in our image-obsessed world. She explores photography not just as an art form, but as something deeply woven into how we experience reality. She questions whether photography helps us engage more with the world or distances us from it. She critiques how photographs replace memory, how they shape what we believe to be true, and whether constant image consumption has dulled our ability to truly see.

Sontag doesn’t write about photography with admiration—she writes about it critically, often uncomfortably so. She argues that photographs are a form of possession, a way of capturing and owning moments, and that they have the power to reinforce stereotypes, manipulate emotions, or even desensitize us to suffering. Some of her arguments feel extreme, and at times, overly cynical. But even when I disagreed with her, I found myself underlining passages and sitting with her words.

It’s not a book for everyone. If you’re looking for something practical, this isn’t it. But for those curious about art, photography, and the role images play in shaping how we see the world, it’s worth sitting with. Whether you agree with her or not, On Photography forces you to pause and think—and maybe, in an era where we’re drowning in images, that alone makes it essential.

Ida Hammershøi: The identity of art's most famous 'faceless woman'

by Lucy Davies

In a rabbit-hole moment while writing this essay, I found myself drawn to a different medium—painting—specifically, the quiet, haunting interiors of Vilhelm Hammershøi. Though I ultimately didn’t use his work, I still want to share it with you, along with this well-written article that captures exactly what I felt while looking at his paintings.

"It's bewitching to see how Hammershøi (1864-1916) took these ordinary things and turned them into modern art. His paintings, which creak with an unforgettable, otherworldly atmosphere, prefigure the work of Edward Hopper and Andrew Wyeth in mid-century America, and the Minimalism movement of the 1960s."

Hey, you made it to the end!

This week, I have to admit—I was under the weather. Honestly, I’m just amazed I managed to send something out. I have to thank my own note-taking habits and planning ahead for that. Turns out, the system I kicked off at the start of 2025 is actually working. Well, look at that.

I have loose drafts of what I’d like to explore seasonally, which I then break down month by month. At the start of each month, I sit down and solidify what I want to think and write about. This means I end up picking up snippets and ideas well in advance of actually sitting down to write.

To layer onto this, I’ve started taking notes in Obsidian, really slowing down the content consumption process. While reading, I’ve always underlined and—depending on the book—scribbled notes into the margins. Now, I have a more structured way of organizing my thoughts. It’s still early days, but I’m already seeing how it helps me connect what I’m reading, thinking about, and creating in a way that feels more intentional.

Should we blindly believe in the asserts by Sontag, Barthes, Benjamin,…? I don’t think so. Isn’t style an invention of the artist?, any either painter or photographer. The artist decides to make his art that way. It’s not done by nature…

Thanks for sharing. Keep going, keep growing. Meaning isn’t found, it’s made.