Leonardo da Vinci Sucked at Finishing Things—Why Are You Worried?

Struggle, time, Leonardo da Vinci, art history, book rec

You Need to Struggle More

I don’t mean suffer. I mean slow down and let yourself experience the process. Struggle is the opposition of forces. It’s the desire to bring an idea to life but having to learn how. It’s writing a paragraph and giving yourself time to edit, re-edit, delete, and write again.

We have a faulty definition of productivity. We think doing is more important than the outcome.

So we post more, take more photos, edit faster, and hit publish before we are ready. On and on.

There’s a balance needed. I’m not telling you to be perfect and never finish something. What I’m saying is that struggle is often a close companion of creativity. It’s a form of problem-solving. And to be able to solve problems, you likely need to give yourself time.

Time to sit and think. To write and delete. To go for walks and meander. To sit in silence and meditate. To fail. To try again. To improve.

Leonardo da Vinci painted the Mona Lisa from around 1503 until his death in 1519. It took years of refining and tweaking. He didn’t sit down and complete it all in one go. In fact, it was never even delivered to the patron who commissioned it. It is considered unfinished.

So why are we all rushing? And perhaps you think you’re not rushing, but isn’t multitasking a form of rushing? Over the past year, as I explored new ideas and took on new projects (such as writing), I fell once again into the trap of viewing every minute of the day as necessitating productivity. It’s the feeling that every action must have a purpose. That’s why I’m strict with my meditation practice at the moment. The fact that I feel I cannot sit down and do nothing for 15 minutes is, for me, worrisome. It tells me I’ve either taken on too much or am living in the future rather than the present.

I’ve been rereading Four Thousand Weeks by Oliver Burkeman, and a quote early in the book has stuck with me: “The spirit of the times is one of joyless urgency,” as written by Marilynne Robinson.

Joyless urgency. That’s not a life I want to lead. So, I’m practicing the act of doing nothing. Here’s what I know about myself: when I meditate, I not only feel better, I act better. I have greater patience, focus, and creativity.

Sitting and meditating may not be painting the Mona Lisa, but Leonardo didn’t have to deal with emails, texts, clients booking Zoom calls, or the toxic relationship our society has with productivity. I imagine he felt just fine sitting down and staring at a canvas without the temptation to multitask. He was fine struggling with the task at hand, taking years to work on it. Now, da Vinci was a perfectionist, I’ll admit. But he could afford to be. He produced masterpieces so stunning that people kept hiring him.

What if we allowed ourselves to struggle a little more in the things we hope to grow in? What would it feel like to focus on one thing with a sense of spaciousness—without the ticking clock in the background? To capture the sensation of being lost in time because we’re so present? For me, the simple act of starting my day early, before the sun has risen, is part of my work right now. I light a candle, wrap myself in a blanket, and sit down to be still before the house truly awakens. It's the feeling of being absorbed in the present, with nothing yet pulling at me. No sense of urgency. I view this as practice. If I can learn to do this, surely over time I will learn to be less distracted as I write, take photos, and learn.

Last week, I mentioned the luxury of a slow process, and this is simply a continuation of that idea. As I remove distractions, sit still, and apply focus, it can feel like a struggle. The temptation to open a new tab, pick up the phone, or get a cup of coffee is constant. I choose to use the word luxury because it implies abundance. A feeling of more than enough. And that’s the life I’d rather lead: one where I am unrushed. Where sitting to think, to be slow, to learn what interests me is part of the process—not an exception.

Things Leonardo da Vinci Didn’t Finish:

The Adoration of the Magi (1481): This large painting was never finished. Leonardo completed the initial design and underpainting but left the details and colours untouched when he moved to Milan.

St. Jerome in the Wilderness (1480s): Although this painting shows his skill in anatomy, Leonardo never finished it, leaving parts of the piece in rough sketch form.

Battle of Anghiari (1503–1506): Leonardo’s attempt to paint a mural in Florence failed due to a new technique he was testing, causing the painting to deteriorate. He abandoned the project, and it was eventually lost.

Things Leonardo da Vinci Did Slowly:

Portrait of Ginevra de' Benci (c. 1474–1478): This early portrait took years to finish, as Leonardo meticulously worked on details like light and texture.

Mona Lisa (1503–1517): Leonardo spent years revising and perfecting this small portrait. He continued working on it long after it was commissioned, never officially delivering it.

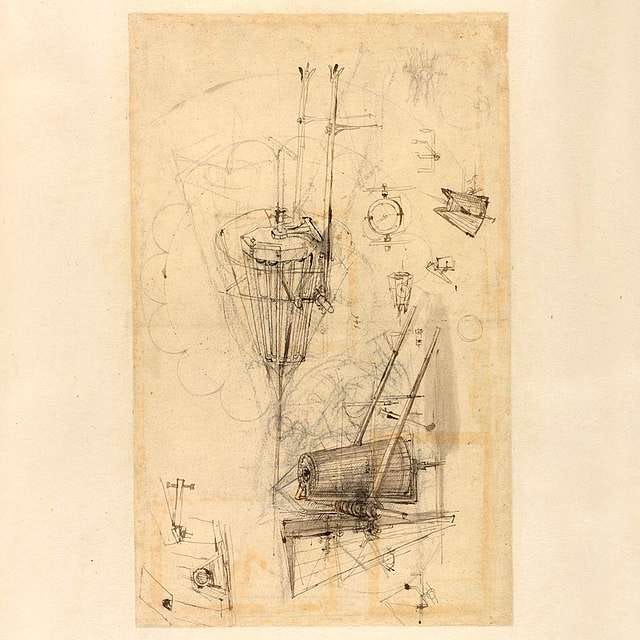

Commissions and Notebooks: Leonardo often missed deadlines, frustrating his patrons. He filled countless notebooks with sketches and observations, but rarely finalized these ideas into complete works.

Architectural and Engineering Projects: His grand designs, like plans for a canal system in Milan, were often delayed or never completed because of his constant revisions.

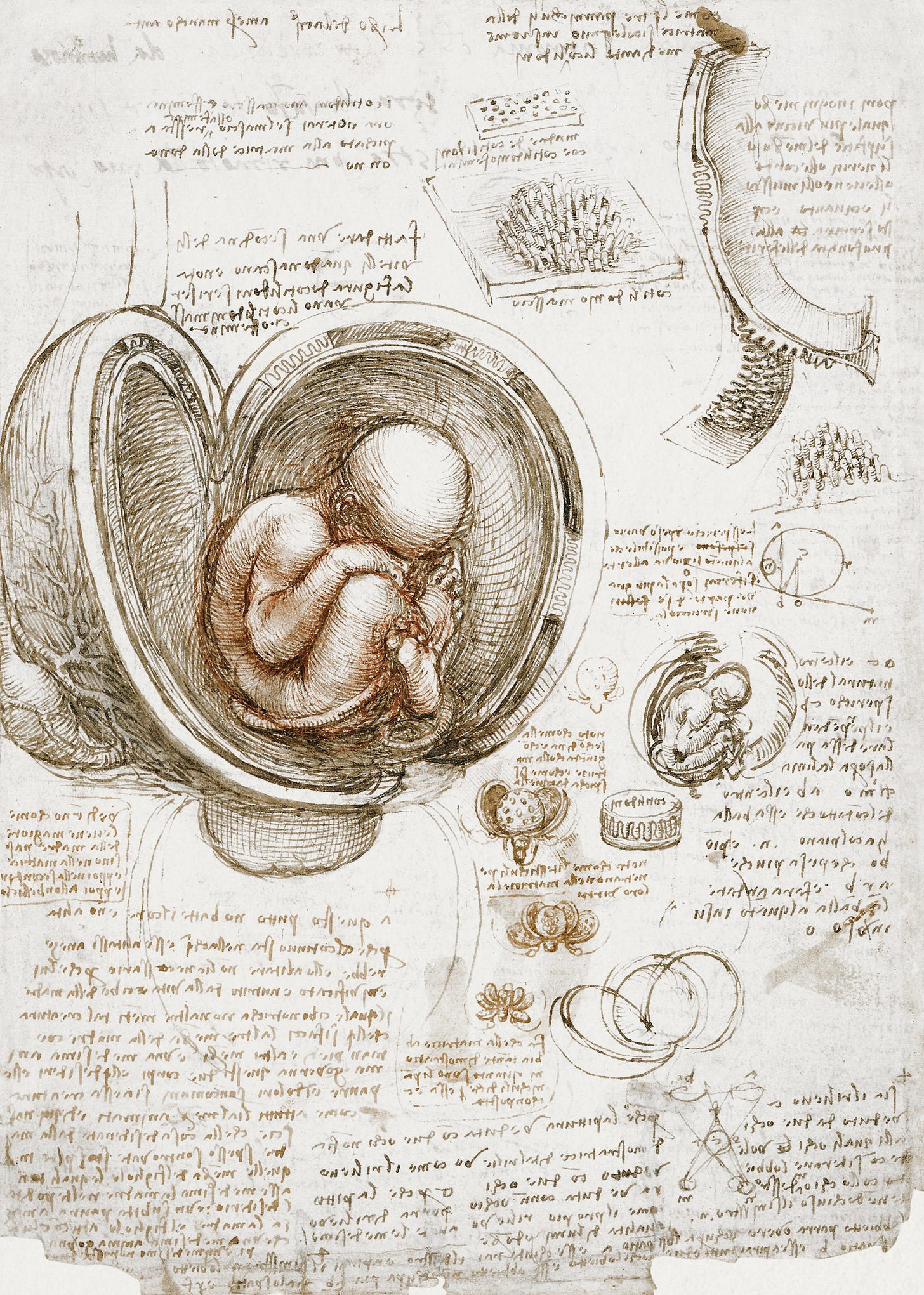

Anatomical Studies: Leonardo made groundbreaking discoveries in anatomy but never published his findings. His procrastination left much of his research unknown until long after his death.

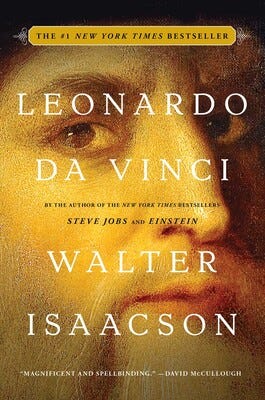

Book Recommendation: Leonardo da Vinci

If you're curious to learn more about da Vinci, I strongly suggest checking out this book. It's a great listen that reveals intriguing details about his life not typically covered in standard art history courses. The book offers a straightforward, no-frills look at the artist's journey and accomplishments.

About The Book:

Based on thousands of pages from Leonardo da Vinci’s astonishing notebooks and new discoveries about his life and work, Walter Isaacson “deftly reveals an intimate Leonardo” (San Francisco Chronicle) in a narrative that connects his art to his science. He shows how Leonardo’s genius was based on skills we can improve in ourselves, such as passionate curiosity, careful observation, and an imagination so playful that it flirted with fantasy. [learn more on the publisher website]

Personal Work

Hey you made it to the end! I have a little secret for you. I have an ongoing project to collect door photos. It's one of those things that started organically while traveling. Doors are fascinating because we can stand in front of them and imagine a story of what's inside. My goal is to capture doors with numbers 1 to 100 over time. I do have some repeat numbers, so the best of the best will make the final cut. I'm not yet sure how the final project will come together, but I'm enjoying the hunt along the way.